Doughnut Economics is a post-growth economic framework developed by economist Kate Raworth that redefines prosperity by balancing human well-being with ecological sustainability. It challenges the dominant economic paradigm that prioritizes GDP growth and instead advocates for a model where economic activity meets essential human needs while operating within planetary limits. Rather than positioning growth as an inherent goal, Doughnut Economics argues for economies that are regenerative and distributive by design, ensuring that human societies thrive without exceeding environmental boundaries or exacerbating social inequalities.

A crisis of economics: why the doughnut was created

The framework emerged in response to the failures of mainstream economic models which either ignore ecological limits or assume that technology and market mechanisms will decouple growth from environmental degradation. Influenced by ecological economics, feminist economics and systems thinking, Doughnut Economics synthesizes decades of research challenging the assumption that infinite growth is both possible and desirable. Kate Raworth first introduced the concept in 2012 in a report for Oxfam, later expanding it in her 2017 book Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist. The model was developed as a practical tool for policymakers, businesses and communities to rethink economic design in a way that ensures social justice while respecting planetary boundaries.

Doughnut Economics was created as a response to two major crises: the ecological crisis, where economies have pushed planetary systems beyond safe operating limits, and the social crisis, where wealth and resources remain highly concentrated leaving large portions of the global population without access to basic needs. The framework provides a way to navigate between these two extremes by designing economic systems that enable well-being without relying on continuous expansion. Unlike traditional economic models which treat environmental damage and inequality as externalities, Doughnut Economics positions these issues as fundamental constraints that economies must work within rather than overcome.

The doughnut model: a map of economic sanity

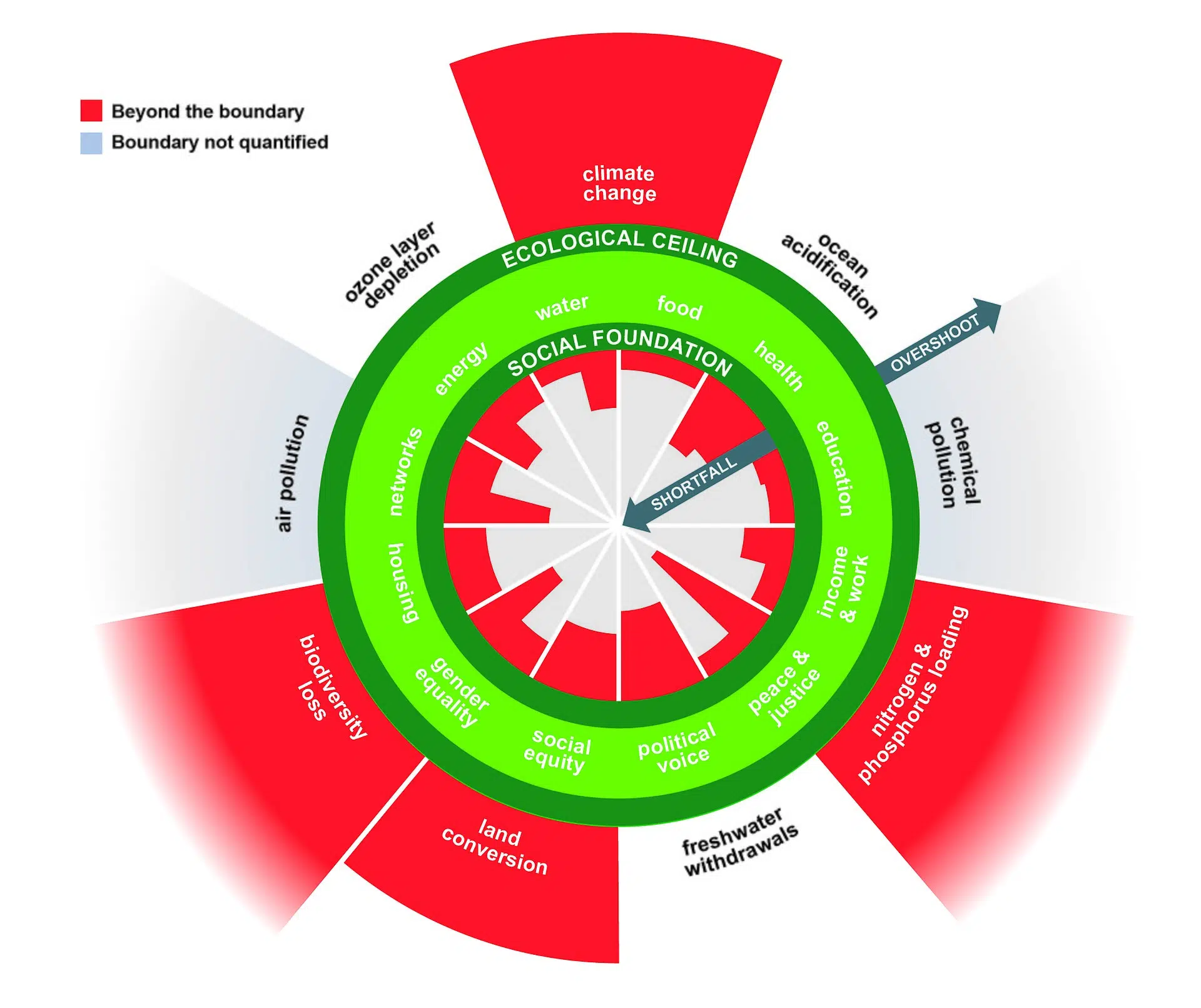

At the center of Doughnut Economics is a visual framework that maps two interdependent thresholds. The inner threshold, or social foundation, represents the minimum conditions required for human dignity, ensuring that everyone has access to food security, clean water, education, healthcare, political representation and meaningful work. Falling below this foundation results in deprivation, exclusion and systemic inequalities.

The outer threshold, or ecological ceiling, is defined by planetary boundaries such as climate stability, biodiversity, freshwater cycles and ocean health. When economic activity overshoots these limits, the consequences ripple directly into the social foundation—climate breakdown leads to food and water shortages, land degradation worsens poverty and resource depletion drives geopolitical instability. Environmental collapse is not just a distant ecological concern but a direct attack on human well-being, making economic justice impossible if planetary limits are exceeded.

The space between these two thresholds—the Doughnut—is not a static zone where economies should aim to “stay within limits.” Instead, it is a dynamic system that requires active transformation. Many economies today already exceed ecological boundaries while failing to provide for basic human needs. Correcting this imbalance requires regenerative economic structures that restore ecosystems while redistributing wealth and resources to strengthen social foundations.

Doughnut Economics rejects the trade-off narrative that pits economic growth against environmental sustainability. Instead of choosing between prosperity and ecological stability, it demands a radical restructuring of economies so that social and ecological health reinforce one another. True progress means ensuring that social foundations are secured not through endless extraction and expansion but through redistributive policies, commons-based governance and regenerative design.

A challenge to designers: what are we really creating?

For designers, Doughnut Economics represents a fundamental shift in design priorities, moving away from profit-driven consumption toward systems-based sustainability and sufficiency. It challenges designers to question whether their work is contributing to economic models that are extractive, disposable and growth-dependent or whether it is helping to build systems that are resilient, equitable and regenerative.

This shift requires moving beyond product-based thinking and into systemic design. Instead of optimizing for short-term sales, designers must develop solutions that extend product lifecycles, support repairability and encourage shared access rather than individual ownership. This means rejecting planned obsolescence, questioning unnecessary technological complexity and designing infrastructures that support circular economies rather than linear production models.

Doughnut Economics also emphasizes the role of design in shaping behavior, institutions and governance systems. It encourages designers to engage in participatory processes, ensuring that those affected by design decisions have a voice in shaping them. This means not only designing sustainable products but also influencing policy, public services, urban planning and digital infrastructures to ensure that economic and technological systems are inclusive, just and ecologically responsible.

Unlike traditional sustainability narratives which often focus on efficiency improvements within existing market structures, Doughnut Economics pushes designers to rethink what is being designed, for whom and why. It prioritizes collective access over market competition, long-term resilience over speed and disruption and regenerative material flows over extractive supply chains. This perspective forces a reevaluation of who benefits from design—whether it perpetuates existing inequalities or contributes to redistributive and cooperative alternatives.

For businesses, the growth trap is over

For businesses, Doughnut Economics represents a fundamental challenge to the assumption that companies must grow indefinitely to succeed. It calls for a rethinking of business models, shifting from extraction and endless expansion toward regenerative and redistributive practices that contribute to planetary health and social equity.

This means moving beyond corporate sustainability initiatives that aim to “green” existing supply chains while maintaining high levels of production and consumption. Instead, businesses must redesign their core economic logic, shifting away from short-term financial returns toward long-term ecological and social value. This requires a move toward circular economy models, where materials are reused, repurposed and shared rather than discarded. It also demands a restructuring of ownership and governance models, moving away from shareholder-driven corporations toward stakeholder-driven enterprises, cooperatives and commons-based business structures.

Doughnut-aligned businesses must also rethink their relationship to labor, shifting away from exploitative, growth-dependent employment models and toward economies that prioritize well-being, fair wages and work-life balance. This means rejecting the ideology of constant productivity increases and instead exploring shorter workweeks, cooperative work models and democratic decision-making structures that distribute value more fairly.

Rather than treating Doughnut Economics as a sustainability initiative to be integrated into existing business structures, companies must recognize that it represents a shift in the very purpose of business. Instead of seeing companies as entities that must extract, grow and accumulate capital, this framework envisions them as stewards of ecological restoration, social well-being and economic democracy. Businesses that fail to adapt to these principles risk becoming obsolete as economies move toward post-growth models that prioritize sufficiency, resilience and justice over expansion and competition.

The next economy won’t look like the last

Doughnut Economics is not merely a sustainability framework; it is a paradigm shift in how economies, businesses and design practices are structured. It challenges the assumption that growth is necessary for prosperity and instead proposes an economic model that balances human needs with ecological limits. For designers, this means rethinking their role in shaping infrastructures, behaviors and economic flows—moving beyond object-based sustainability to systemic transformation. For businesses, it requires a fundamental restructuring of ownership, production and value creation, shifting from infinite expansion toward regenerative and redistributive models that operate within planetary boundaries.

As the world faces accelerating ecological crises and widening social inequalities, Doughnut Economics provides a practical and politically transformative alternative to the failing logic of growth-based economies. It is not a minor reform but a structural rethinking of what economies are for and how they should function—offering a vision where design, business and governance work together to ensure a thriving future for both people and the planet.